Message for the Sixteenth Sunday after Pentecost, Year C (9/28/2025)

Luke 16:19-31

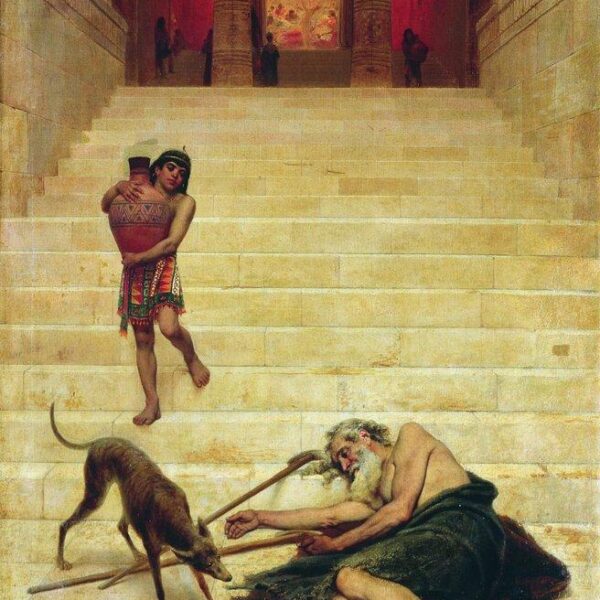

Pay attention, and you’ll discover that no one takes the Bible literally, not even those who claim they do. The Bible said it; I read it; that settles it, right? But when’s the last time you heard a fundamentalist preacher condemn wealthy people to hell on account of their wealth? It’s right there in black and white. According to the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, those who suffer want in this life will be comforted in the next, and those who enjoy abundance in this life will suffer in the next: “Child,” Abraham calls to the rich man in Hades, “remember that during your lifetime you received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in agony.” Cross-reference that with the Sermon on the Plain: “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God… woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation.”[1] It checks out!

Or does it? The promise of heavenly solace is certainly good news for the poor, precisely the kind of message Jesus insists on preaching.[2] But something about this story suggests that it’s not meant to be taken literally; the imagery of consolation and condemnation is not simply about balancing the economic scales in eternity. Still, if Jesus’ parable isn’t a blueprint for the afterlife, then what is it?

If you suspect the metaphor of heaven and hell serves a more nuanced purpose, you’re on the right track. Jesus is dead serious about the injustice of life in the world as we know it. Lazarus is already living in hell, he implies, while the rich man locks himself away in a private heaven. Languishing just a few steps from the rich man’s home, Lazarus might as well be a world away. In other words, the second half of the story is a reflection of the first; the “great chasm” separating the two men in eternity is but an exaggeration of the social distance between them on Earth. So take note, Jesus says; the gap between luxury and destitution is tragically wide; in this life rich and poor are as far apart as heaven and hell.

It occurs to me, then, that this parable isn’t about wealth and poverty only, but also isolation and neglect. The rich man’s great error isn’t simply his accumulation of resources, but his obliviousness to the poor person in his midst. Indeed, the two men are quite literally neighbors– the rich man knows where Lazarus resides, and even knows his name– yet he has utterly lost sight of him. In fact, no one pays any mind to Lazarus except the dogs.

The great tragedy, then, isn’t simply the economic disparity between the two main characters, but their needless separation. The rich man has every opportunity to traverse the short distance to meet Lazarus in his circumstances, but for whatever reasons he just doesn’t.

And there we find ourselves in the story.

What is it, do you think, that detaches us from the suffering all around us? Why do we avoid our neighbors? Certainly, there are forces at work to distract us from each other, pushing us into our cars and homes and private relationships. There’s a lot of money and power to protect against more equitable distribution.

But I wonder if it’s also a question of habit. Social distance is ingrained, and we simply don’t think to break out of our routines in order to see and understand other people. Is it possible that it just didn’t occur to the rich man to acknowledge and befriend Lazarus?

Priya Parker is an expert in creating transformative gatherings. Think of all the bad meetings and awkward parties you’ve attended. The organizers of those meetings and parties could have used Parker’s help. In her book, The Art of Gathering, she argues that social distance has the power to undermine a gathering unless the organizers intentionally equalize their guests:

[Excerpts from pp. 87, 89-90]

Friends, the chasm is wide. There is much work to be done to bridge it, but the first step is to acknowledge social distance where it exists, and collapse it where we can. God has given us into each other’s care, and that is both a challenge and a gift. Renowned spiritual teacher Ram Dass puts it beautifully: In this life, “we are all just walking each other home.” That is to say, if our eternal destiny is tied up together, it’s because our lives are already tied up together here and now, whether or not we live like it. So let’s live like it.

[1] See R. Alan Culpepper, The New Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. IX, 315.

[2] Luke 4:18.

Liturgy © 2022 Augsburg Fortress. All rights reserved. Used by permission under OneLicense # A-706920.

Liturgy © True Vine Music (TrueVinemusic.com). All rights reserved. Used by permission under CCLI license #11177466.

“Gather Us In”; text and music: Marty Haugen, b. 1950; © 1982 GIA Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission under OneLicense # A-706920.

“Build a Longer Table”; Text © 2018 GIA Publications, Inc., giamusic.com. All rights reserved.

“In Christ Alone”; Keith Getty | Stuart Townend; © 2001 Thankyou Music (Admin. by Capitol CMG Publishing). All rights reserved. Used by permission under CCLI license #11177466.

“We Come to the Hungry Feast”; Text and music © 1982 Ray Makeever, admin. Augsburg Fortress

“Lord, Whose Love in Humble Service”; text: Albert F Bayly, 1901-1984, © Oxford University Press; music: The Sacred Harp, Philadelphia, 1844; arr. Selected Hymns, 1985, © 1985 Augsburg Fortress. All rights reserved. Used by permission under OneLicense # A-706920.